Steamscapes: Asia by Eric Simon is a steampunk setting guide for Savage Worlds. It is the second a series, following Steamscapes: North America. It gives us a unique take on Asia, bringing steamworks and independence to the far east through stories, mechanics, and alternate histories.

Seriously, that is some badass cover art.

The cover immediately grabs you. You’ve got an o-yoroi where the helmet's glowing eye mask looks like it incorporates a breathing apparatus and some sort of power cord is draped over the left arm. Although it may be considered a typical action pose, that similarity helps you immediately spot the anomalies that identifies it as a steampunk portrait.

The interior art is a bit of a mixed bag. There’s not much consistency. Some pages have art similar to silk painting, woodblock prints, and even some old photographs, whereas others have almost cartoon like characters. Each on its own is fine, but mixing them up makes for a strange juxtaposition.

For navigation, the book has an index and the PDF version also has bookmarks. If I could quibble here it is that at the top level the bookmarks are just labeled “~ Chapter 1 ~”. That doesn’t tell me what the chapter is about. So it doesn’t do much to help me navigate until I start looking at the headers within each chapter. Speaking of those chapters…

Chapter 1 explains the book, giving the reasons behind this particular alternate history. The authors strive to remove or minimize colonial and other western influences so that native characters will have greater agency. This helps frame the historical changes so that even if you disagree with some of them, you understand the reasoning behind them. Where this wasn’t necessary, I appreciated the candor as it immediately set my expectations for what I was to about read.

Chapter 2 sets out three stories to show you what sort of adventures you might get up to. More importantly, they introduce the apothecary, highlight the opium trade, and introduce some setting specific technologies. In this way the stories prime you for new mechanics and the setting. I found it unfortunate that all the stories are about China instead of showcasing a greater variety of cultures, particularly from some of the lesser known ones, like Sarawak.

Chapter 3 introduces new mechanics. First up is the apothecary (a new Edge), who is initially described through an extensive history mixing real and alternate history. The apothecary edge is really just an enabler for buying the healing or chemical engineer (gunpowder and poison) skills and their related edges. The latter path struck me as the more interesting of the two. The healer’s edges are all static. As you grow you don’t get anything new to do, you just get better at it. Comparatively, the chemical engineer’s edges are full of enablers that you unlock as your skill grows, allowing you access to new types of detonators, new types of poisons, and the like. It gives chemical engineers a nice sense of “I learned something new and cool”.

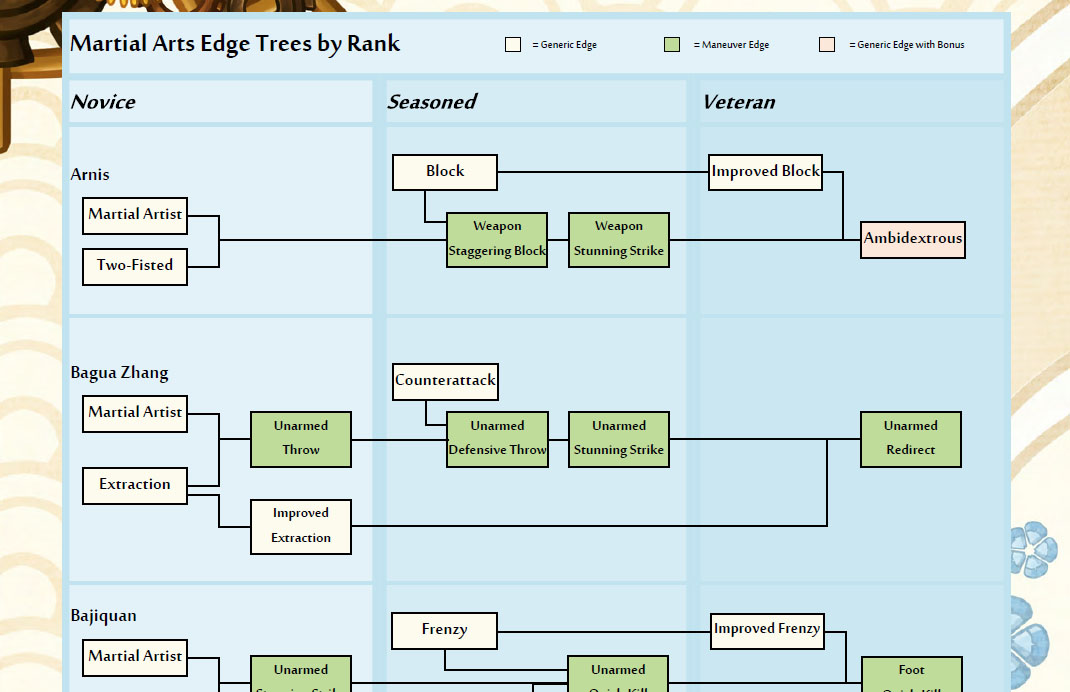

Chapter 4 brings the reader a plethora of martial arts. It does this by introducing new fighting maneuvers and then building edge trees out of the maneuvers, both new ones and existing one from Savage World. It is an approach that I like, even prefer ever since first exposed to it back with AD&D’s Oriental Adventures, as it represents the stages of learning a martial arts style, rather than just letting you jump around. However, it can also be a bit confusing as martial arts styles will inevitably overlap, sharing maneuvers between each other. Here things benefit greatly from a graphic representation of the martial arts edge trees by rank, showing you, at a glance, how to advance within your chosen style(s). This is an approach I hope the series sticks with both because I like it and because it would be weird to have only this set of edges function this way.

This is what the martial arts edge trees look like, giving you a guide for your path to power at a glance.

This chapter also includes new equipment. You get various eastern weapons, new vehicles, and rockets. What I cannot comment on is whether any of the mechanics presented here suffer from power creep. Often supplements follow a pattern where that which is published later presents mechanical advantages that are more powerful than that which has come before. New powers and fighting styles always run this risk. At least where fighting styles are concerned the introduction of new maneuvers here is balanced by locking you into development trees. None the less, Steamscapes: Asia is the second in the Steamscapes series, and I haven’t read the first.

Chapter 5 gives the reader the long anticipated full alternate history rundown. Given the focus on China up to this point, I was a bit surprised it started with India, but I was also happy for the change. It continues with the usual suspects: China, Japan, and Korea. Then it delves into countries that usually get little to no air time: Philippines, Vietnam, Thailand, Burma, Singapore, Malaysia, Sarawak, and Brunei. I was very glad to see them included.

Regarding the setting material itself, I found myself in the position to actually use my minor in Asian & Middle Eastern Studies from my undergrad days. At the outset I was looking forward to seeing the book’s take on certain key events, like the sepoy rebellion, the French backing of what is now Cambodia vs. Mueang Thai, the unification of Japan, Commodore Perry's visit, the Mongol invasion, and even the Boxer Rebellion if the timeline got that far (it didn’t, but that’s ok). The important thing about all of these events and more is that although you, me, and the author may all have wildly different takes on how they might unfold in an alternate history, the different facets of the alternate history must work together. If you tweak one event in history, the changes will cascade. When you are writing any setting, but alternate history especially, it is easy to get caught up in how cool it might have been if one event or another went differently and then not deal with the consequences. Steamscapes: Asia gets this right.

This section is thorough, and it includes some of the earliest history of each region. I’m not sure how much of that is necessary, as opposed to just focusing on the differences. Historical research nowadays can be done very easy via the internet so just seeing the differences in a timeline may be more useful as it would help you zero in on what you need to know. This does sort of exist in the index, where several events are listed by year, but it is incomplete.

That said, one thing the narrative approach does well is that it addresses that initial concern I raised, which is to say that it is internally consistent. Reading through it you can see real world events peppered with changes that grow; you get to see all the changes strung together in a coherent narrative. However, because of the narrative approach, this section reads a bit like a history text book. Where I am totally fine with that, it may turn off other readers.

Perhaps the thing that I most felt missing from this section was guidance as to how the characters fit in, how they should behave, and what directions are open for their stories. The histories are fairly tight narrations that don’t always showcase the options they make possible. But the next chapter helps address this.

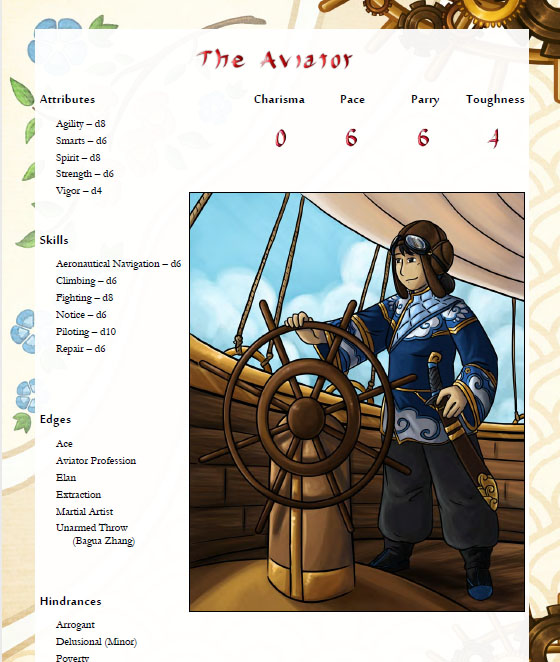

One of the several new example characters introduced with chapter 6.

Chapter 6 tries to take everything else in the book and tell you how to start throwing it together. Unfortunately, despite the aim of this chapter, it actually comes off as the weakest of the bunch.

It does well by giving you advice on what players might experience. For instance, it talks about how likely and under what circumstances you might see the new airship types, emphasizing how rare it would be to ever see one of China’s ten Dragon class airships. Unfortunately, where the information it has is great (I would even say necessary), it is also very thin. There’s a lot more that could be talked about here.

When it gets to advice for characters, it actually hits a point of contention for me. The importance of cultural identity is downplayed, even thrown out to a degree. This comes after many pages of rich history describing the impact of identity, be it personal, religious, or national. Putting aside the real world for a moment, in the game world, being Korean, for instance, has real weight to your character. Even if you try to ignore it, that identity will shape how Chinese, Japanese, English, and Russian NPCs will all act towards you (the five of them are in a bit of a kerfuffle). Where, yes, “people are basically people wherever you go,” there is a profound difference in the mindsets of people based on their cultural upbringing, and dismissing that is, for me, the wrong way to go. That said, the book totally gets it right when it cautions you to avoid certain stereotypes, but it stops short of giving you positive role models to follow.

This chapter ends with three short adventures that illustrate how the setting can be used. It does a good job covering an array of locales and countries: Burma, India, and Manchuria (the part of China that Japan is invading). It also covers themes that include mercantilism, religion, and war. These scenarios do a good job of illustrating how the book can come together, but they aren’t really a replacement for explaining that.

Overall, Steamscapes: Asia is a solid setting book. Even if you don’t use Savage Worlds, its alternate history is a fun read, re-imagining the far east with enough historical twists and steam tech to prevent the colonial European powers from taking control. Where the world goes from there is your story.